For their solo exhibition "Four Disobediences / 네 가지 무례함," at N/A Gallery Mira Mann has created a new body of work exploring the circulation of signs, symbols, meanings, memories and values, and addressing issues of gender identity.

The exhibition centers around the three channel video 'mother may recall another,', filmed in 2022 in the Museum of east Asian Art in Cologne, in Mokpo, their mothers hometown, and in Düsseldorf in the artists studio. Mann narrates the story of Shim Cheong, a Confucianist educational tale on filial piety and female self-sacrifice including multiple actors and actresses who embody the character of Shim Cheong: the artist themselves, their cousin, sister, the drag artist Chang13 and a group of K-pop dancers. Other appearing characters are Mann's mother and aunt, and the Pansori interpret So Sol-I, all of whom chose unusual or unforeseen life paths, embodying the four disobediences as narratives that deviate from the expected norm or standard.

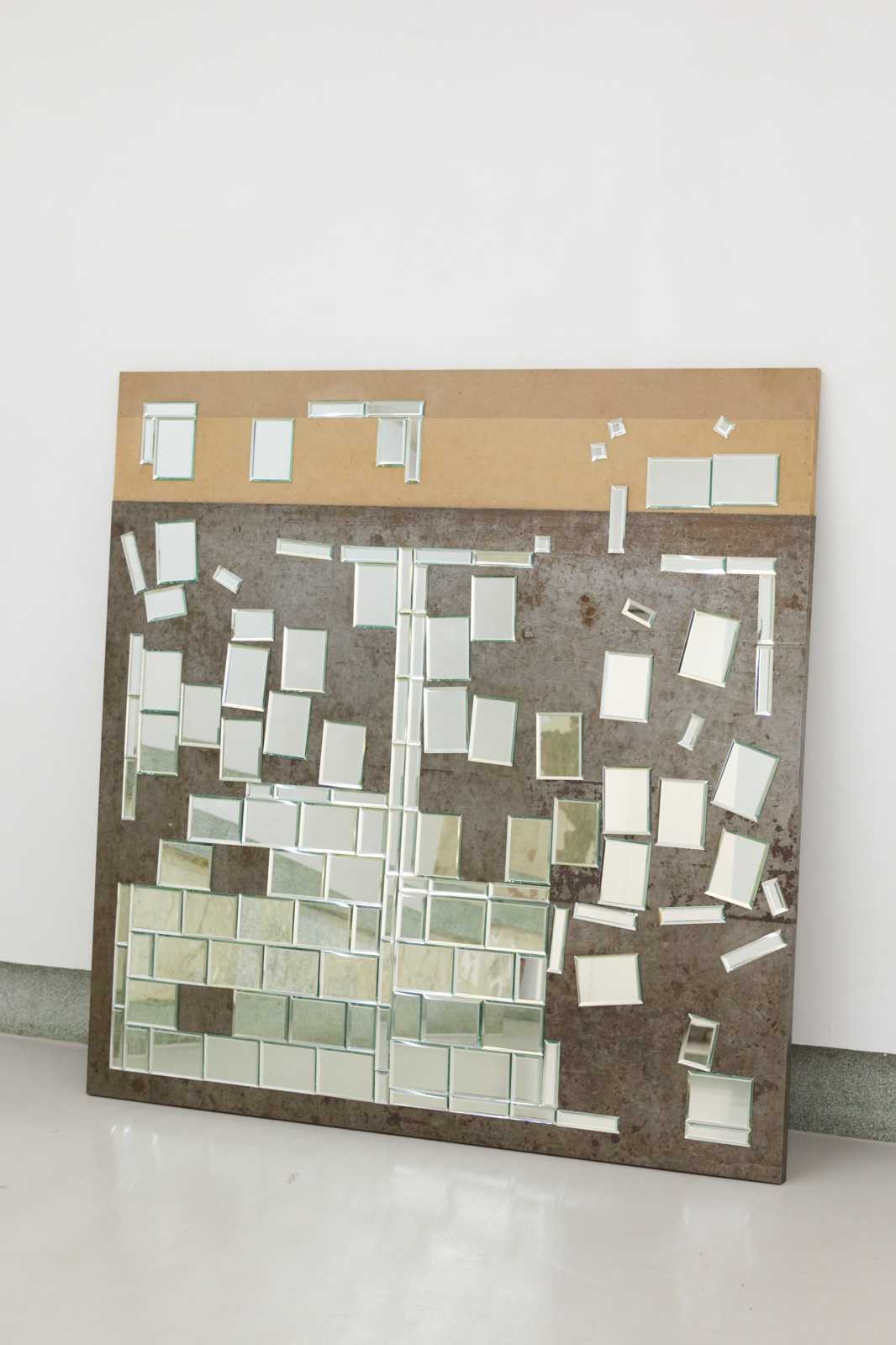

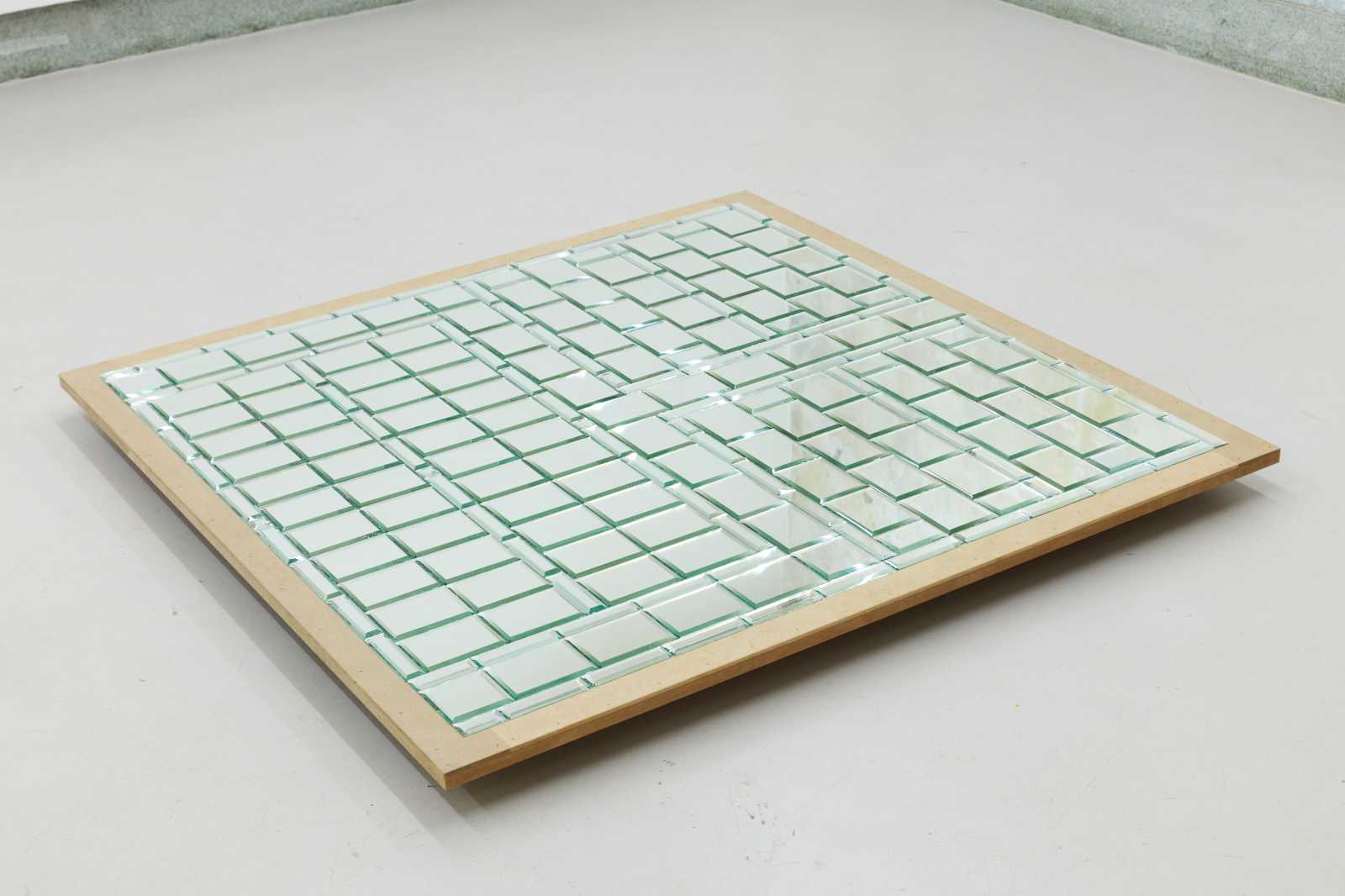

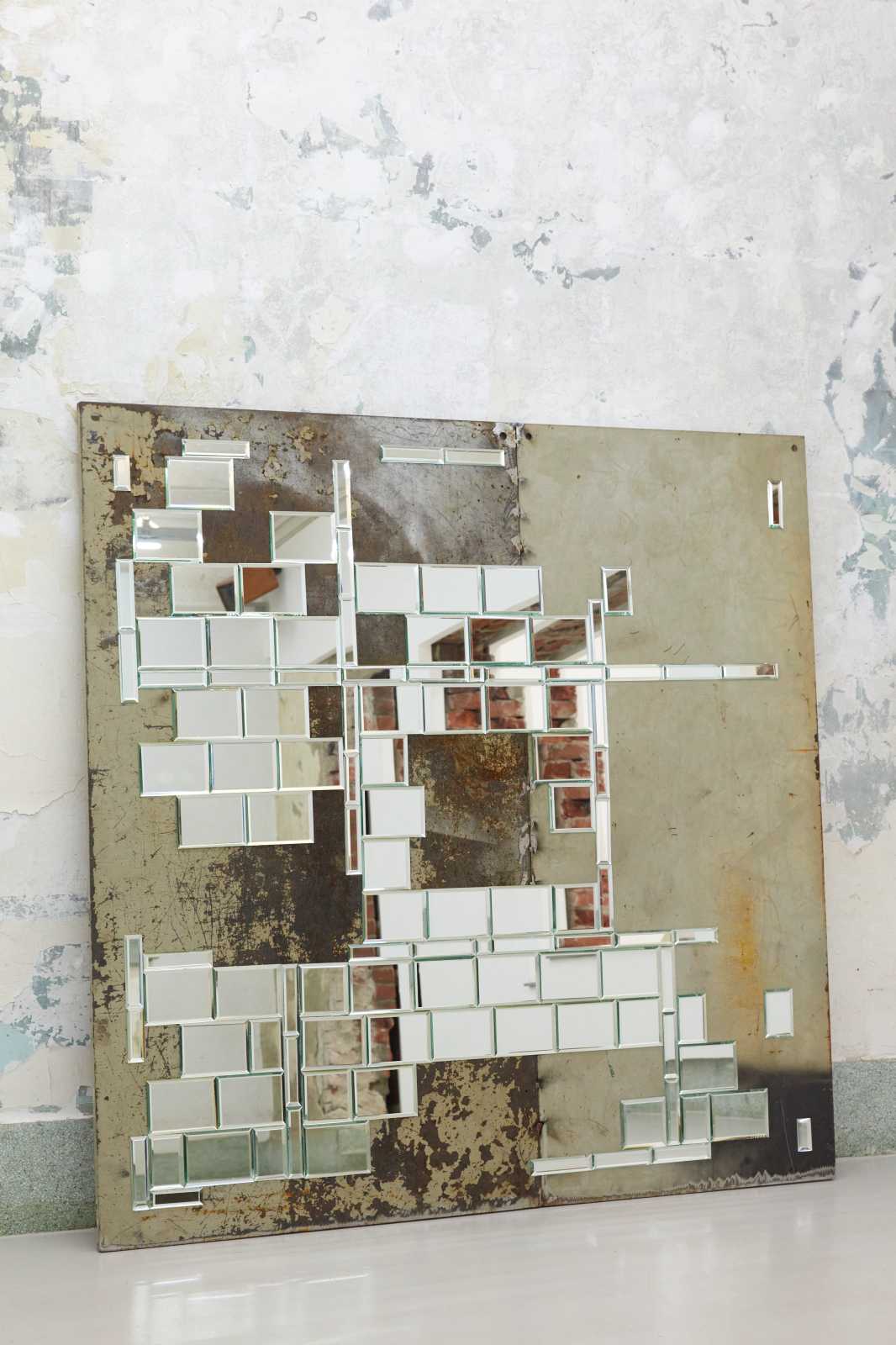

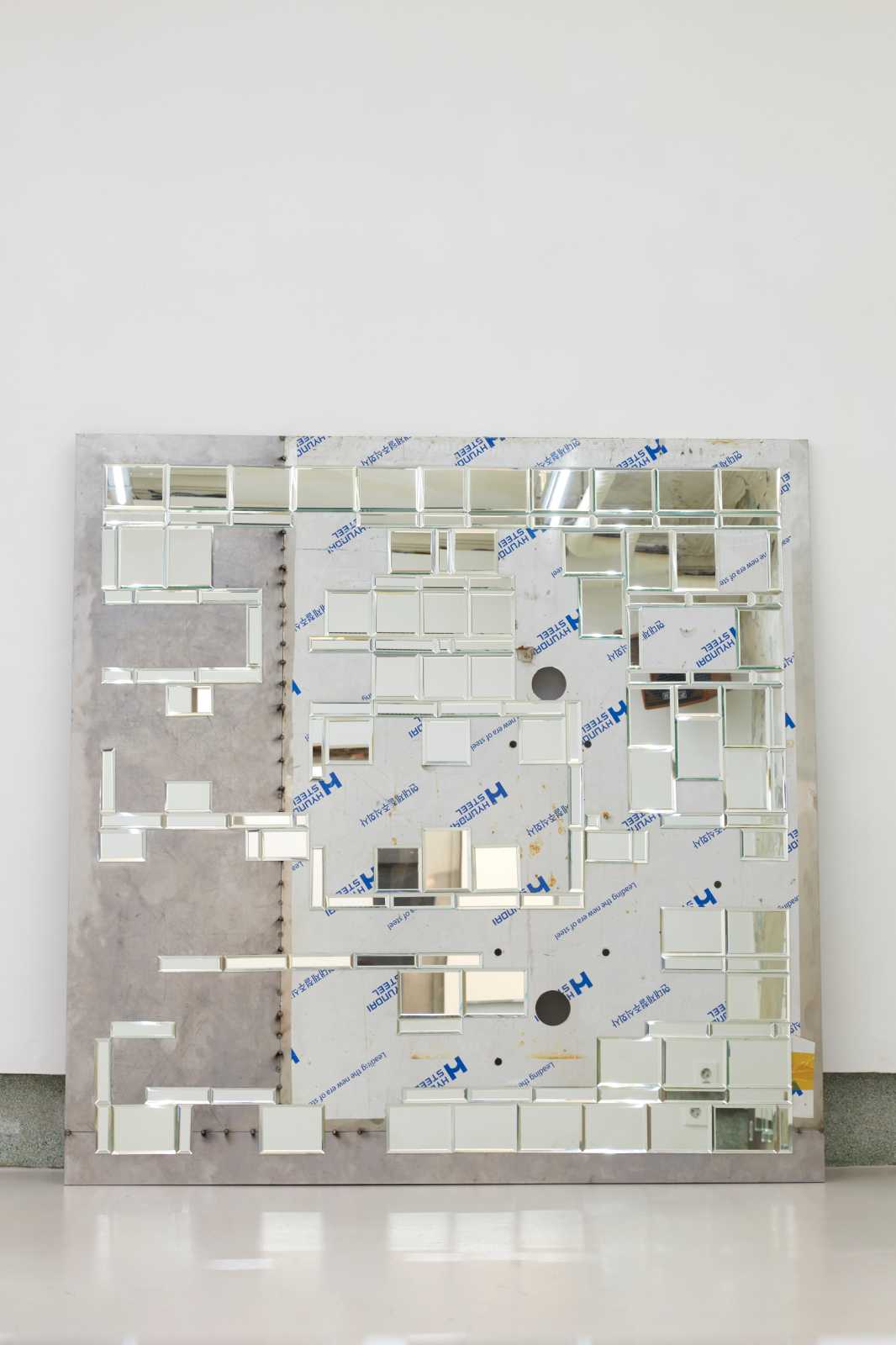

While seeking to explore and confuse the construction of memory and self-narratives, as well as architectures of remembrance and colonial continuities in the city of Mokpo, the video further contends with female labor in the globalized history of cultural production, entertainment, and transactional aspects of gifts, offerings and sacrifices.The new series of works, conceived during the artists residency in Seoul titled ‘neither one nor the other / 間’, ‘stripper / 脫’, ‘changer / 變’ and revolutionary love, mon cheri / 共 consists of four panels which are each based on an ornamentally abstracted Hanja character, composed of mirror tiles on surfaces found in the neighborhood of the gallery, old metal sheets of workshops and raw construction wood. This latest work of Mann took inspiration from the tile patterns in Seoul’s subway stations, showing Hanja characters that are related to the confucian four pillars of destiny and propagate values such as filial piety, health, marriage, luck, power and longevity. Mann suggests four alternative characters: 脫 (tal), meaning to break free, withdraw, escape, degrow, remove, take off, strip"; 間 (gan), meaning "gap, break, between, mixed up, spy, secret agent, moonlight peaking through a door " and "non-binary"; 變 (byeon), meaning "change, strange, become, turn into" and "transformation through times"; and 共 (gong), meaning "empathy, togetherness, community and sharing. Carrying ambiguous meanings these four disobedient signs unveil impertinency against propagated social norms playfully subvert the signs and ornamental structures.

Mira Mann (b.1993, Frankfurt am Main, DE) lives and works in Düsseldorf, graduated from Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2021. Their time based, site-specific modes of working and discursive scenographies evolve around transcultural relations of human and non-human agents and the glitches they generate between experience and memory, reality and fiction.

Their work was shown in solo exhibitions, <Four Disobediences / 네 가지 무례함>, N/A Gallery, Seoul (2023),

, Galerie Drei, Cologne (2022), and , Simultanhalle, Cologne (2020) and in group exhibitions such as, Cork Street Banners, Serpentine, London (2023), , HEIT, Berlin (2023), , DeAppel, Amsterdam (2022), , Brücke Museum, Berlin (2022), <when it moves strengthening it’s skin>, Kunstverein Bielefeld, Bielefeld (2022), , Galerie Max Mayer, Düsseldorf (2022), , Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf (2022), , Wien (2022) and others. Besides the four disobediences

Text by Nicholas TammensIn producing mother may recall another (2023), Mira Mann travelled to South Korea with their mother Hanju Yang, visiting sites from Yang’s childhood in Mokpo before she immigrated to Germany in the 1980s. The conceit of this trip was to produce a contemporary version of the pansori tale

Shimcheongga, with Mann, their cousin, sister, fellow queer artist Chang13, and a cast of German K-pop dancers standing in for the character of Cheong who is renowned for her sacrifice to her elders. In the classic version of the tale, this takes multiple forms, from wage labour, to the care of her blind father, the prostitution of her body, and finally, her martyrdom that ultimately restores her father’s vision. In Mann’s retelling, embodied by the various performers of differing ages, Shim Cheong appears as a queered version of Korean femininity, dressed in a costume composed of a deconstructed school uniform designed by the artist and Anna R. Winder. Introduced by Christian missionaries in the late 19th century, such uniforms are emblematic of the modernisation of Korean dress, a change that was rooted in forms of standardisation, Japanese imperialism and Western influence, changes that are also mirrored in the developments of modern military uniform. These changes in the customs of dress came at a time during the abolishment of the stringent Confucian caste system of the Joseon Dynasty, signalling a transformation in how personhood was regulated by the state and enacted by individuals. While Pansori emerged as an artform rooted in folk tradition and shamanic ceremonies, by the 18th century it became a functional part of the Joseon Dynasty as an art form imparting Confucian ideology. This function became less relevant with the modernisation of society, as new art forms and media took the place of traditional arts in promoting societal narratives, gender roles, and moral principles. Even while certain aspects of Confucian ideology persist today in Korean gender hierarchies and social norms, the way in which its lessons are transmitted have changed form, inhabiting new modes of performativity, for instance, in TikTok videos or serial streaming platforms.As a Confucian moral tale, Shimcheongga stresses the duty one has to one’s elders; in the traditional version of the tale, the protagonist submits herself to the sea, transforming her into a lotus flower. The miraculous transformation of Shim Cheong restores the sight of her blind father and many others without sight. Transposed to a different context, we might ask, how are we to understand such a message? Mann’s trans- cultural experience as someone born to a Korean mother in Western Germany suggests that a new set of meanings can be constructed out of the tension of two cultures, and the estrangement—or in Bertold Brecht’s terms Verfremdungseffekt—that allows us to see what may only remain latent or overlooked in both the story of Shim Cheong and Yang’s narrative in the film. In Mann’s version, the position of the father is notionally inhabited by her mother: the control of the camera—and in effect the gaze itself—is put in the control of Yang, held by her or passed onto family members. The ocularity that is restored in the traditional tale is instead embodied by her mother’s direction of an early 90s home video camera that she bought the year the artist was born.

While traditional pansori focuses on the technical feats of its singer- performer, who embodies the positions of all characters and narrator. In Mann’s work, the performer remains unseen. Performed by the Berlin- based Sol-i So, her song provides the narrative framework of the pansori to scenes showing the various embodiments of Shim Cheong visiting sites in Mokpo with historical importance to Yang. For instance, they visit an imperial building in the style of Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the architect famous for redesigning Paris, which was once the site of the Japanese imperial government and later a prison during the rule of Park Chung Hee; the former highschool of Yang, where Mann performs the school’s daily military style march under the direction of their mother’s memory; the harbour where she used to skip school, and it’s brick factory that was once operated by the Japanese occupiers; they search for the house in which Yang was born; visit supermarkets, and usedbookstores. Alongside Mokpo, we see scenes from the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, Köln, a site in which the Western fetishisation of Asian femininity is displayed in objects obtained through colonial trade; and a performance by Iridescent Wings, a group of German K-pop dancers whose genuine engagement with the popular culture of Korea is mediated by the internet and their presence on social media.

Also an immigrant to Germany, Sol-i So originally trained in Korea before feeling burdened by the traditional limitations of pansori teaching. For Mann, it’s important to note that So’s singing could be seen as unconventional for pansori traditionalists. At times improvisational and partly working from memory, So’s delivery speaks to Yang’s experience as an immigrant to Germany, but also the construction of a narrative about her emigration from Korea. This suggests a link between memory and the imaginary, a representation of Mokpo and the radical transformation of Yang's home country since the 1980s. Visiting these sites from her youth, before her immigration to Germany, this investigation into her own past asks how place, built environment, and memory are intertwined. By documenting this process of return, we get an impression of the inconsistencies of one’s own recollections. For Mann, such a story occupies the same narrative space as a moral tale imparted from mother to daughter, one that concerns origins but also a set of moral lessons concerned with family, obligation, debt, and sacrifice. In watching Mann’s film as a work of art, it's possible to imagine that we’re placed within the narrative of Shim Cheong, as an omniscient outside character endowed with the power of aesthetic judgement. From this position, we might conclude that Mann implies that the martyrdom of Shim Cheong is analogous to a kind of sacrifice made by the artist. In other words, before Shim Cheong’s objectification, she remains outside the gaze of the authority and power of the father, or in this case the viewer. Shim Cheong’s sacrifice is a process similar to that of the artist: by stepping into the role of a character or producing objects themselves, Mann objectifies, and as a result, makes artistic process and thinking visible to the observant viewer.

In each of Mann’s works, there is the suggestion that the artist’s practice as a performer is always present in how an object is staged or the action of a video is captured. As Mann’s work demonstrates—for instance in the mirror work 바리데기-D [paridaegi-D] (2023)—there is a theatricality in the viewing of contemporary art that places the viewer in an active role, as a participant, as an actor. While this “theatricality” was something famously levelled against Western minimal art by the American critic Michael Fried, who saw it as a debasement of modernism’s claim on the autonomy of the artwork—something apart from the world, self-contained, medium specific, without moral or political purpose—subsequent practices of performance art, conceptualism, and installation have made theatricality a strength in challenging such conservative assumptions. While this modernist vision of artistic practice relied on a philosophical grounding in the Western tradition that assumed a split between subject and object, from the perspective of Eastern and Western traditional arts alike, such a distinction is not naturally assumed nor sustained by medium specificity. Rather, an art such as pansori, which has both a moral purpose and is the result of various art forms working in unison, is more equivalent to strategies in contemporary art than it might first appear.

As is well known, the performer in pansori embodies multiple roles, shifts between genders, and occupies a place within the social world of the pansori and one notionally outside it, as its narrator. This is analogous to the adaptability of the women who occupied such roles among others, often from the class of Kisaeng. As Mann outlines:

“Kisaeng were courtesans, entertainers, performers, and sex workers with a complex social, political, and cultural role during the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, yet they have often been written out of the history books. Kisaeng of the court were registered as government slaves, and consequently they can be traced back to the eleventh century in Korea. They mostly held the rank of cheonmin, the lowest class, together with butchers, shoemakers, other entertainers, and slaves. Either born into the role through a kisaeng mother or sold by their families, their social status was tainted. However, in order to become intelligent and charming companions to the wealthy and influential, they underwent a strict education from an early age at specialised institutions and were trained in various fields of fine and performing arts such as dance, poetry, singing, reading, and painting, as well as medical care. Kisaeng from Jeolla-do were trained in and performed pansori. Although they were enslaved, and their lives very much determined by their position in society, they were expected to develop their own style and artistic expression, to cultivate an identity through their skills, and to express themselves through art, dance, music, and poetry. Their role as a highly educated, sexually promiscuous travelling entertainer and conversationalist with access to public events and political negotiations – outside of the strict gender roles of Confucianism that kept women confined to the domestic space – is therefore exceptional in comparison to that of all other women of the time.”

We might ask, is the irreconcilable contradiction of these women, living in bondage slaves yet expected to develop their own individuality, harsh analogy for the perceived free will that individualism promotes in our own time?. The characterisations that occupy Mann’s work suggest that the speak to broader themes of performativity and self- representation that function in our modern capitalist societies, as ways of representing ourselves, that are more of an obligation than a perceived choice. In the world in which we operate, socialise, work, fall in love, raise families, and march to the grave, we are surrounded by images and our own role in constructing them. The obligation to self-design, to self-characterise, to create and promote an image of ourselves through media is a habitual part of our participation in society. As Mann’s work shows, how we perform this image, in our fashion, our gender expression, or social position, moral claims persist and are built into the narratives that we construct and the stories that we tell each other.

N/A 갤러리에서 열린 개인전 <네 가지 무례함>을 위해 미라 만은 기호, 상징, 의미, 기억, 가치의 순환을 탐구하며 성정체성 이슈를 다루는 새로운 작품들을 선보였다.

3-채널 비디오 작품 'mother may recall another(어머니는 다른 게 생각날 수도 있다)'이 전시의 중심을 이루는데 이는 2022년에 쾰른의 동아시아미술관, 목포, 어머니의 고향, 그리고 뒤셀도르프에 있는 작가의 스튜디오에서 촬영하였다. 만은 효심에 대한 유교적인 교육관을 바탕으로 한 심청전을 여성의 자기희생의 시각으로 이야기하며 심청을 묘사한다. 여러 배우들이 심청을 연기하는데 작가 자신과 사촌, 여형제, 드래그 아티스트Chang13, 그리고 K-pop 댄서 그룹이다. 또한 다른 인물들로는 만의 어머니와 이모, 판소리 해설가 소솔이가 등장하는데 모두 독특하거나 예상치 못한 인생 경로를 택한 사람들로서 예상 범위 내의 규율과 기준에서 벗어나는 네 가지 무례함의 내러티브를 몸소 구현한다. 기억과 자기서사의 구성 그리고 목포시의 추모 관련 건축과 식민지의 연속성을 탐구하는 동시에 이에 대한 혼란을 부여하기 위해 이 비디오 작품은 문화사업, 엔터테인먼트 분야 속의 여성의 노동 문제를 다루고 선물, 제물, 희생의 거래적 측면도 생각해본다.

서울에서 작가가 경험한 아티스트 레지던시 중에 창안한 신작 시리즈인 ‘neither one nor the other(이도저도 아닌) / 間’, ‘stripper(스트리퍼) / 脫’, ‘changer(변하다) / 變’ 그리고 'revolutionary love, mon cheri(혁명적 사랑, 자기야) / 共' 는 네 패널로 구성되어 각기 한자의 추상화된 장식성을 바탕으로 갤러리가 위치한 동네에서 주운 거울 타일, 낡은 철제판과 목재로 만들었다. 만의 최신작인 이 시리즈는 서울 지하철역 타일 패턴에서 영감을 받았으며 사주팔자와 관련된 한자를 표현하며 효, 건강, 결혼, 행운, 권세와 장수의 가치들을 전파하고자 한다. 또한 만은 네 가지 대안적 한자들을 제안한다: 脫 (탈)은 탈주, 철수, 회피, 축소, 제거, 떠남, 벗음의 의미; 間 (간)은 간격, 휴식, 사이, 혼재, 스파이, 비밀요원, 열린 문 사이로 빼꼼히 들여다보는 달빛의 의미; 變 (변)은 변화, 기묘, 무엇이 되다, 무엇으로 되다, 제3의 성, 시간의 흐름에 따른 변환의 의미; 그리고 共 (공)은 공감, 유대감, 공동체, 공유의 뜻을 지닌다. 이러한 애매모호한 의미를 담은 네 가지 불복종의 기호들은 사회적 규율에 대한 반항심을 드러내며 기호와 장식적 구조를 유희적으로 전복시킨다.

미라 만(1993년생, 독일 프랑크푸르트 출신)은 현재 뒤셀도르프에 거주하며 창작을 한다. 2021년에 뒤셀도르프 쿤스트아카데미를 졸업하였다. 시간을 바탕으로 한 장소특정적 작업 모드와 산만한 듯한 시노그래피는 인간과 비인간 주체간의 문화횡단적 관계과 이들이 일으키는 경험과 기억간, 현실과 픽션간의 불협화음을 주목한다. 개인전은 <Four Disobediences / 네 가지 무례함>, N/A Gallery, 서울 (2023), <mother may recall another', Galerie Drei, 퀼른 (2022), 'Wild and Wanton', Simultanhalle, 쾰른 (2020)에서 전시하였고 그룹전은 Cork Street Banners, Serpentine, 런던 (2023), 'stile gazing', HEIT, 베를린 (2023), 'super feelings', DeAppel, 암스테르담 (2022), 'open house', Brücke Museum, 베를린 (2022), 'when it moves strengthening it’s skin', Kunstverein Bielefeld, 빌레펠트 (2022), 'age of self', Galerie Max Mayer, 뒤셀도르프 (2022), 'another eye', Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, 뒤셀도르프(2022), 'Phantasmatic Riff', 빈 (2022), 등이 있다.

네 가지 무례함 외

니콜라스 탐멘스'mother may recall another'를 제작하기 위해 미라 만 Mira Mann은 어머니 양한주와 함께 한국을 찾았다. 어머니 양한주가 1980년대 독일로 이민 가기 전 어린 시절이 보냈던 그녀의 고향 목포. 'mother may recall another'는 우리가 알고 있는 효녀 심청의 이야기, 판소리 '심청가'를 미라 만이 현대에서 다시 품어낸 작업이다. 이 현대판 심청가에서는 옛날 옛적 희생적으로 노동을 하며 눈먼 아버지를 봉양했고, 급기야 자기 몸을 팔아서 까지 아버지의 눈을 뜨게 했던 효녀 심청 자리에 미라 만과 그의 사촌, 동료 퀴어 아티스트 Chang13, 독일 케이팝 댄서들이 등장한다. 이렇듯 미라 만의 심청가에는 단 한 명의 심청이 등장하는 것이 아니라, 안나 윈더가 재해석한 교복을 입고 다양한 나이대의 여러 인물이 퀴어적 한국 여성성을 현현한다. 19세기 말 기독교를 전파하러 한국에 왔던 서양 선교사들에 의해 도입된 교복은 획일적인 모습의 한국 근대화의 일면을 보여줄 뿐만 아니라, 근대 군복의 형성사와도 그 결이 맞닿아 있다. 조선시대 엄격한 유교적 신분사회의 폐지와 함께 등장한 의복 관습의 정형화는 어떻게 국가가 개인을 규제하려 했고 그것이 어떤 모습으로 실행되었는지를 보여준다.

판소리는 민속 전통과 무속에 그 뿌리를 두고 등장하였으나 18세기 무렵이 되어서는 조선의 유교적 이념을 담아 표현하는 기능을 하였다. 19세기 말 근대화가 시작되면서, 새로운 예술 형식과 미디어의 출현으로 인해 판소리는 사회적 관념이나 성 역할, 도덕적 가치를 표현하는 매체로서의 자리를 내어주게 된다. 그러나 유교적 이데올로기는 여전히 현대 한국 사회에서 사회적 통념과 젠더 위계질서로 그 모습이 남아있다. 다만 이념을 전달하는 방식과 형태만이 변이하여 이제는 틱톡 비디오나 스트리밍 플랫폼이라는 새 미디어를 통해 송출될 뿐이다.주인공인 심청이 바다에 몸을 던진 후 연꽃으로 변신하는 심청가는 부모에 대한 효도와 어른 공경이 강조된 유교적인 미덕을 따르는 내용이다. 판소리 심청가는 바다에 몸을 던지고 연꽃으로 변신하는 심청의 이야기를 유교적 미덕인 효를 강조하며 읊어간다. 아버지와 또 다른 장님들의 시력을 회복시켜 빛으로 인도한 심청의 기적적인 이야기. 우리는 이 이야기를 어떻게 또 다른 맥락으로 읽고 이해할 수 있을 것인가. 독일에서 한국인 어머니 아래 태어나, 이중문화 환경 속에서 성장한 미라 만의 경험은 다른 문화의 확장과 응축 사이, 그리고 소외에서 — 혹은 베르톨트 베르히트가 말했듯 소외효과Verfremdungseffekt 에서 — 새로운 의미가 구성될 수 있음을 보여준다. 우리가 심청과 미라 만의 어머니 양한주의 서사 안에 숨겨진 이야기를 볼 수 있는 것도 그 덕인 것이다. 'mother may recall another'에서 아버지의 위치에는 어머니 양현주가 자리한다. 그의 손에 들린 혹은 그가 통제하는 카메라에 의해 전달되는 그의 시선을 통해서 말이다. 어머니 양현주가 작가가 태어난 해, 90년대 초입에 구입한 가정용비디오 카메라로 기록한 이미지가 고전 심청가의 회복된 시력으로 들어오는 빛의 서사 자리에 들어앉는다.

전통 판소리는 하나의 소리꾼이 무대에 나와 모든 등장인물과 화자의 연기를 구현하는 재주를 뽐낸다. 이와 대조적으로 'mother may recall another'에서는 서솔이 소리꾼의 모습은 보이지 않고 다만 그의 소리만이 청각적 구성물로 남아 이야기의 서사적인 틀을 제공하게 된다. 심청의 소리는 그렇게 어머니에게 의미 깊은 목포의 여러 장소를 방문한다. 일본 제국 총독부 목포 지부가 소재지였고, 후에 박정희 통치 기간 동안에는 감옥이었던 파리를 재설계한 것으로 유명한 건축가 조르주 외젠 오스만 스타일의 제국주의 양식의 건물, 70년대 어머니가 교련 수업을 받았고 작가가 어머니의 기억을 통해 재현했던 목포여자고등학교, 어머니가 수업을 빠지고 친구들과 놀러 갔던 목포 대반동 해변, 일본식민지 때 내화 벽돌을 생산∙반출하던 조선내화공장의 폐허 등에 말이다. 그들은 어머니가 태어났던 집, 어린 시절 오갔던 슈퍼마켓, 헌책방 등도 찾아간다. 또, 영화 속에서는 어머니의 고향인 목포 이외에도 아시아 여성성에 대한 서양의 페티시화를 보여주는, 식민지 무역을 통해 획득한 물품이 전시된 독일 쾰른의 동아시아 미술 박물관과 인터넷과 소셜 미디어를 통해 한국 대중문화에 진정으로 몰입하며 참여하는 독일 케이팝 댄서 그룹인 Iridescent Wings의 공연도 등장한다.

서솔이는 독일로 이민가기 전, 한국에서 판소리 교육을 받고 창법을 연마한 전문 소리꾼이다. 그는 전통 판소리의 창법에서 중압감과 한계를 느꼈고 이를 벗어나기 위해 독일 이민의 길을 선택했다. 서솔이의 소리가 전통적 창법과는 색다르다는 점이 미라 만에게는 중요했다. 완성된 창법에서 탈피하여 즉흥적이고 파편적인 기억에서 나오는 그의 소리는 어머니 양한주의 이민자로서의 경험에 공명할 뿐만 아니라 서솔이 자신의 이민 서사를 구성하는 청각적 틀이다. 서솔이의 소리는 고향인 목포의 표상, 1980년대 이민 이후 어머니 고국의 급진적 변화가 담긴 기억과 상상의 연결고리를 암시한다. 독일로 이주하기 전 어린 시절의 서사가 담겨있는 장소들을 방문하며 자신의 과거에 대한 답사는 장소와 환경 그리고 기억이 어떻게 얽혀 있는지 묻는다. 회귀 과정의 기록에서 우리는 기억 사이에 오류가 있을지도 모른다는 인상을 받는다. 작가에게 이는 어머니가 딸에게 전하는 도덕적 설화나 자신의 출생, 가족에 대한 의무, 부채, 희생과 관련된 일련의 도덕적 이야기와 같은 서사 공간을 차지한다.

미라 만의 영화를 예술 작품으로 보고 있자면, 관람자로서 그 서사 안에 속해있다는 생각이 들게 된다. 미적 판단을 할 힘을 부여받은 전지적 시점의 외부인으로서 말이다. 이런 시각에서 보자면 마치 미라 만이 심청의 자기희생은 예술가의 희생에 유사하다 말하는 것 같다. 다시 말하자면 심청은 대상화되기 전까지는 아버지의, 혹은 관객의, 권위와 권력의 밖에 놓여있는 것이다. 심청의 희생은 예술과의 그것과 유사하다. 미라 만은 캐릭터의 역할에 들어가거나 오브제를 제작함으로써 개념화하고, 그 결과로 유심히 살펴보고 있는 관객의 시선 안에 작가의 창작 과정과 사상을 가시화한다.

미라 만의 작업에는 늘 작품이 연출되는 방식이나 영상이 포착되는 방식에 행위자로서의 예술가의 모습이 암시되어 있다. 그의 거울 작품인 <바리데기-D>(2023)에서도 볼 수 있듯 관객에게 참여자나 배우 같은 능동적인 역할을 부여하는 현대 미술을 관람하는 행동에는 연극성이 내포되어 있다. 이러한 “연극성”을 미국 비평가 마이클 프리드는 세상과 분리되고, 윤리적 정치적 목표 없이, 독립적이며 매체 특정적인 모더니즘이 가진 예술 작품의 자율성을 저해하는 원인이라 간주하여 서구 미니멀 아트를 비평하는 기반으로 삼았지만, 행위 예술, 개념주의, 설치 미술을 통해 연극성은 오히려 그러한 보수적 관념에 도전하는 힘으로 자리잡았다. 모더니즘 예술은 주체와 객체를 분리하는 이항 대립적 서양의 철학에 기반에 의존하였으나 동서양 전통 예술의 관점으로 보자면 그러한 이항 대립적 구분은 매체 특수성에 의하여 지탱되지 않는다. 오히려 도덕적 이야기를 담은 채 여러 예술 형식이 조화롭게 우러난 판소리와 같은 예술은 언뜻 보기보다 현대 미술의 전략과 더 가깝다고 할 수 있다.

알려진 바와 같이 판소리의 소리꾼은 성별을 넘나들며 여러 역할을 구현하면서 판소리 안에서뿐만 아니라 판소리 밖에서도 관념적으로 서술자로의 자리를 차지한다. 이는 유연하게 여러 역할을 맡아야 했던 여성들, 기생의 모습과 유사하다. 이에 대해서 미라 만은 다음과 같이 설명한다.

“ 기생은 고려와 조선시대에 기녀, 연예인, 예능인, 성 노동자로 복잡한 사회·정치·문화적 역할을 담당했지만, 역사의 기록에서는 지워지고는 했습니다. 관청의 기생은 그곳의 노예로 등록되었기에 11세기까지 그 기록을 거슬러 찾아볼 수 있는데, 대부분 최하층인 천민의 계급에 속했습니다. 백정, 갖바치, 기타 재인이나 노예들과 함께 말이죠. 기생 어머니에게서 태어나 기생이 되거나, 가족이 팔아서 기생이 되었거나 사회적 지위는 매우 낮았죠. 그렇지만 부유하고 영향력 있는 사람들을 상대하기 위해 아름답고 총명해지려 어려서부터 전문 기관에서 엄격한 교육을 받았습니다. 다양한 분야의 훈련을 받았어요. 무용, 서화, 노래, 독서, 의술까지 말이죠. 전라도의 기생은 판소리를 훈련받았다고 합니다. 기생은 노예였고 사회의 신분을 탈피할 수는 없었지만 자신만의 기교 형태와 예술적 표현을 갈고 닦아 예술, 무용, 음악, 시를 통해 자신을 표현했습니다. 높은 수준의 교육을 받고, 성적으로 자유로운 방랑하는 예인이자 공식 석상에서나 정치적 협상에서 참여할 수 있던 기생은 여성을 가정에 울타리 안에만 두던 유교적 성역할의 밖에서 존재하던 극히 예외적인 존재들입니다. "

기생들은 속박 속에 살면서도 자신만의 개성을 발전시켜야 하는 극복 불가한 모순 속에서 그들의 삶을 이어갔다. 이 여성들의 삶에 내재한 사회적 모순은 우리 현대인의 자유 의지를 통한 자아실현의 허상에 비유할 수 있지 않을까?

미라 만의 작업에 형상화된 인물 특성을 살펴보면 현대 자본주의 사회에서 자기표현과 자아실현에 대한 영역과 그 방식들은 자유로운 선택이라기보다는 의무에 가깝다는 것을 암시한다. 우리는 태어나 관계를 맺고, 일하고, 사랑에 빠지고, 가족을 이루고 언젠가는 무덤에 이르기까지 이 세상을 사는 동안 자신에게 주어진 역할과 이를 구성하는 이미지에 둘러싸여 있다. 미디어를 통한 자기 디자인, 자기 특성화, 자기 홍보에 대한 의무는 우리가 사회에 참여하는 방식이 되었다. 미라 만의 작업이 보여주듯, 우리가 어떤 이미지를 보여주는지, 어떤 방식으로 행하는지, 어떤 성역할, 사회적 역할을 보여주는지는 우리가 구성하는 서사에 포함되어 서로에게 말해주는 이야기가 되어 지속된다.