Festival of Spirits, Garden Funeral

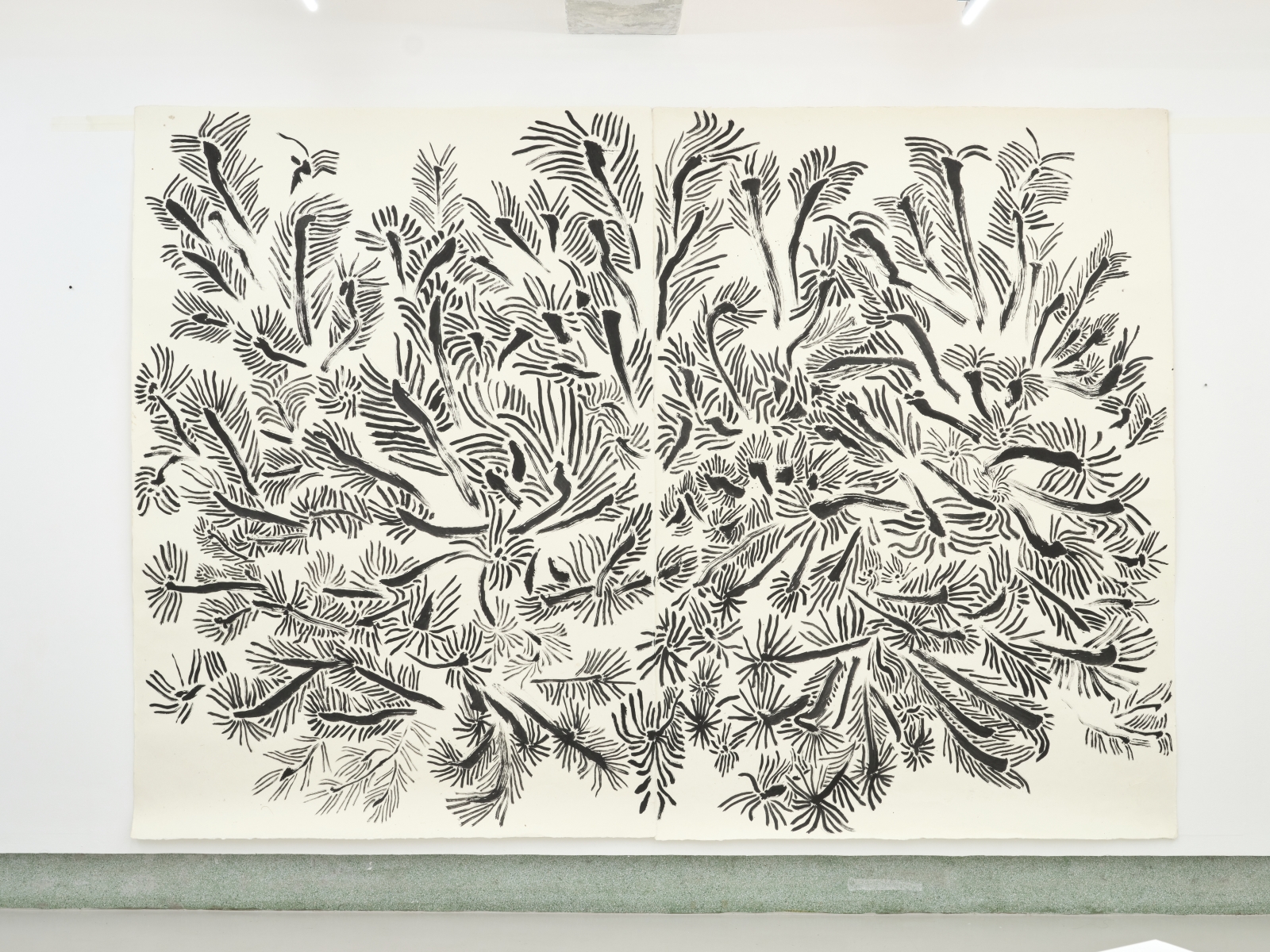

JaehunFestival (2023–) is a relay work that began when the artist Yeonså Cha intercepted the series of the same name, Festival (2006–2017), which her late father, Korean painter Cha Dongha, had been creating. Yeonså cut the hanji that Cha Dongha had dyed for his Festival series with tailoring scissors, shaped it, and attached it onto panels covered with silk. The forms that the artist creates through collage have their origins. They are the unclaimed bodies in forensic book plates, the silverfish dried and stuck in damp and dark places, and the poetic words that relay scenes of endings in various ways.

If Cha Dongha’s Festival prepared a poetic space for the dead or the left behind through the rhythm of colour planes rather than clearly showing the informational value of the represented subject, then Cha Yeonså’s Festival gathered lives outside the unwritten rules and, by “transcribing”, built her own lexicon of poetic words. (Cha Yeonså repeatedly visits rubbish dumps where all the dregs of the world pile up to find her “friends,” and this image resembles a solitary spider cultivating its inner force through extreme (極) and poison (毒).) The translated originals, while maintaining only the minimum of their original form, gave the impression of shadows that

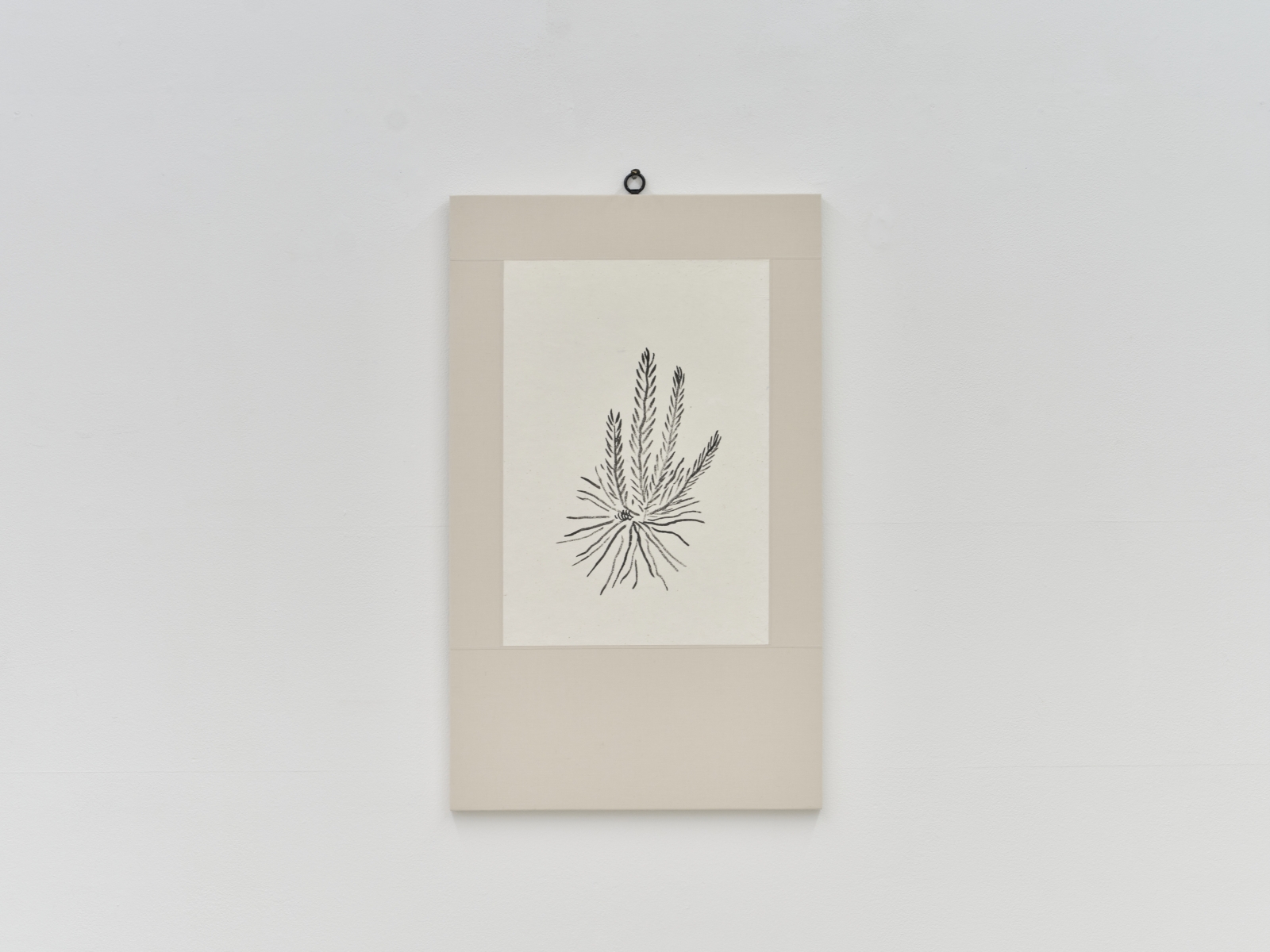

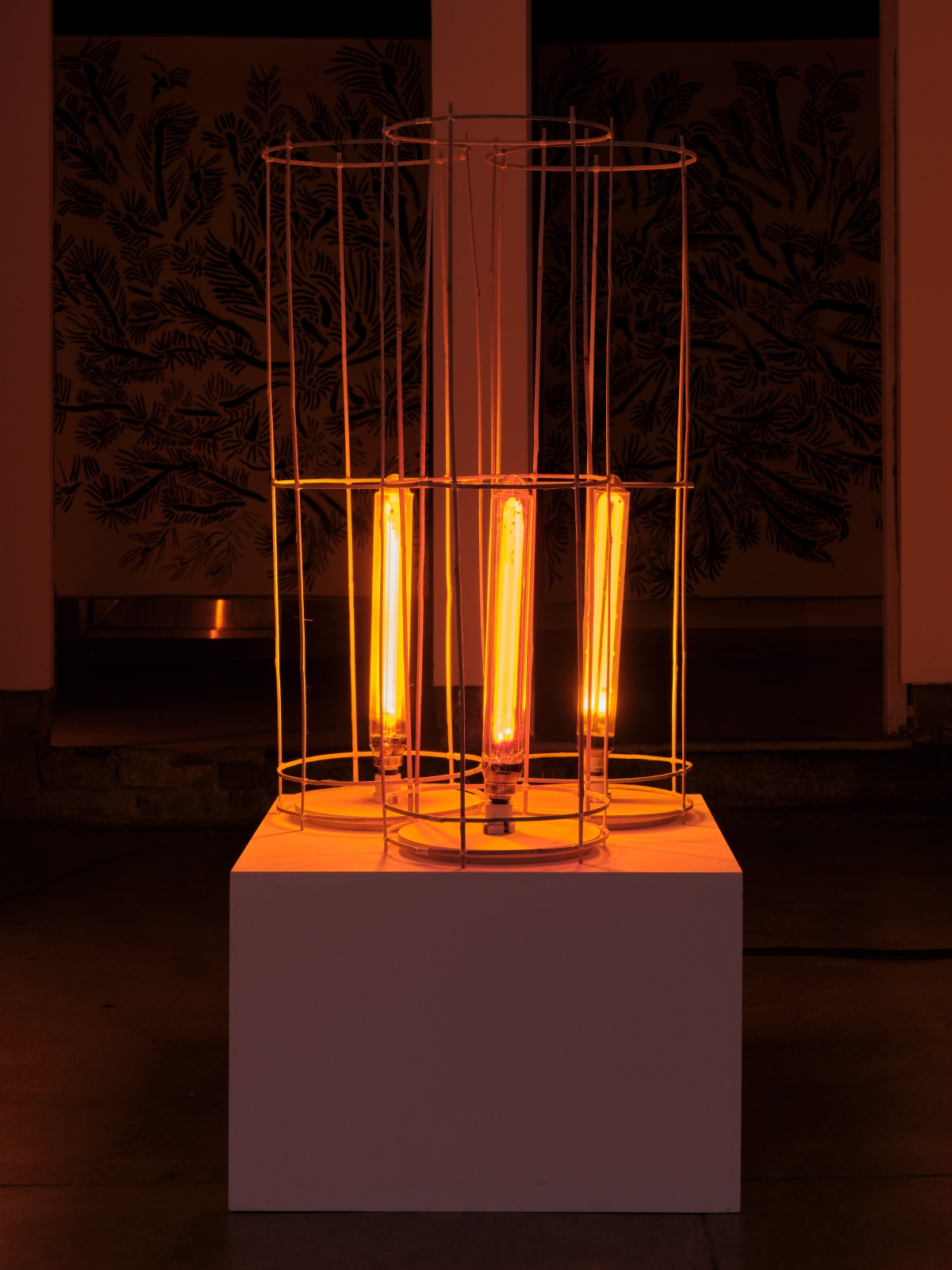

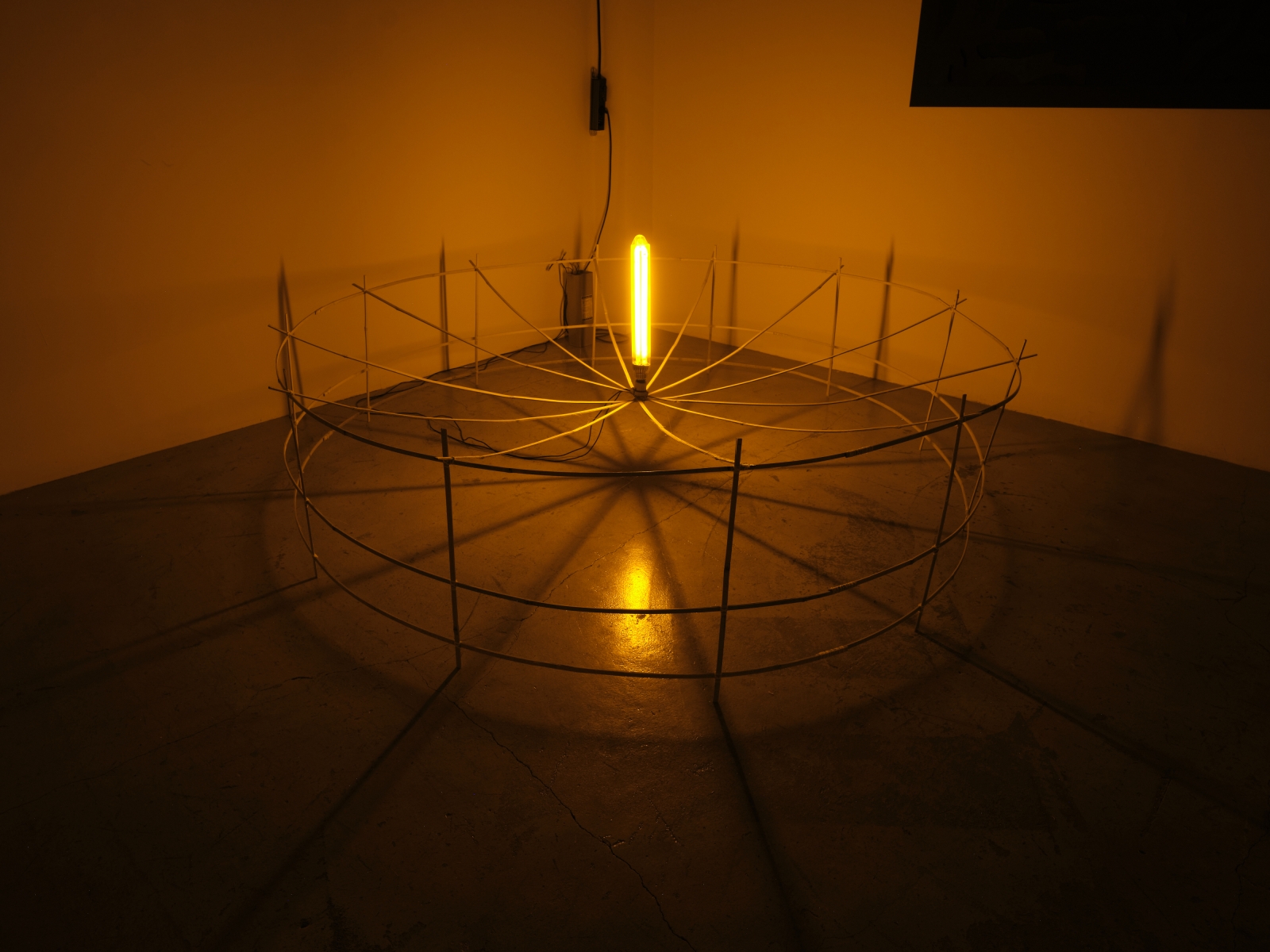

had spread wide, and the artist always seemed excited at casting the actors for her “shadow play” drawn from the tragedy that is our world.And in 2025, after Soman (小滿), the solar term when things begin to fill from small beginnings, director Jinhyeok Oh and I visited the artist’s studios in Seoul and Namyangju in turn. There, I saw (perhaps the very works you are looking at now in this exhibition) Festival Wagon, Wet/Dry Wheel, Tower, Tree, and Spring Onion Flower. They were of a different nature from the Festival works of Yeonså I had followed until then, and they entrusted themselves to a procession that could not be caught by the words attached to earlier works. Newly born, newly cast friends of Yeonså. Chilly and warm at the same time.

From these Festival works, similar yet different from the earlier ones, what I sensed was a spatiality I had never felt before. Unlike the earlier works, which drew particular characters, scenes, and gazes into the frame, the newly chosen subjects of transcription—stone pagoda, tree, spring onion flower—were breathing their energy into the space outside the frame. It was not difficult for me to come to the thought that this was Cha Yeonså’s garden, and I noted that the newly chosen subjects were in fact the elements that make up the garden of Cha Dongha’s (late) studio. (If in 2023 and 2024 the main imagery that composed Festival was corpses, then in 2025 the garden in Namyangju appears as another imagery.)

Because it takes place in the place the father left behind, and uses the materials he left, Cha Yeonså’s Festival has often been regarded as a work of mourning for her father. But even if the death of Cha Dongha became the admission ticket to that world, it would be a stretch to read Yeonså’s act of cutting hanji as a rite for him. Nor do the Festival works shown in this exhibition feel like actual acts of mourning for the souls of the corpses, as did those produced in 2023. Where, then, is the gathering point of Festival, which continues to unfold and transform?

Following the artist’s consciousness, I encountered Zhuangzi’s concept of Wu Sang Wo (吾喪我). “I have buried myself.” And, “I have lost myself.” This philosophy contains the meaning that one must lose the wo (我), the self created by society, in order to find the true wu (吾), the self. Seen through this principle, Yeonså’s Festival was the building of the landscape that will surround her at the time of her death. Having encountered countless forensic plates, criminal profiling materials, and the poetry of Kim Eun-hee, she must have drawn her own death scene thousands of times; for her, the work is the translation of the house in her mind into reality. The orphans, each going their own way, pause for a breath in this garden punctuated by real images of death.

As the artist once said, “Through my work I have repeatedly experienced reconciliation with hostile objects,” the act of tending a garden also becomes a way of facing the pains of reality. Cha Yeonså cuts apart (1) the old version of Festival created by Cha Dongha, offering it to corpses and spirits, and (2) transcribes the garden in Namyangju, thereby expanding the space in which her friends’ bodies can

frolic. Recently, for the sake of her work, she has been residing for several days at a time in the house within the Namyangju garden. From there she has sent me images of newly made works or passing thoughts by text, and not long ago she told me that the seongjusin (the household god) inhabiting the house had begun to murmur again. To me, those words sounded like the sign of yet another Festival. For on her timeline, the image of the garden–Festival is like an unfixed casting mould, constantly changing.A related, curious story: at present Festival is held by only two collectors besides the artist herself. After entrusting the works to these two collectors, the artist confessed that the corpses depicted within the frame soon began to feel like portraits of the collectors. By this account, Festival is none other than the collector’s portrait or dress code. This exhibition, Hum Bomb, Hum Bomb, Hum Bomb Hum, serves as the introduction to the Festival in the form of a garden; until the artist’s new Festival begins after this exhibition, we as viewers are free to devour this garden greedily or remain aloof, as if alone. That she has opened her garden as a park for our time to be possible, and that she regards Festival as the collector’s portrait, calls forth the public dimension of the Festival Cha Yeonså organises.

정령들의 축제, 정원 장례식

글 재훈<축제>(2023~)는 작가 차연서가 자신의 아버지인 故 한국화가 차동하가 만들어 오던 동명의 연작 <축제>(2006~2017)를, 가로채며 시작된 릴레이 작업1이다. 차동하가 자신의 연작 <축제>를 위해 염색해 두었던 닥종이를 차연서가 재단용 가위로 자르고, 모양을 만들어, 비단을 바른 패널에 붙이는 방식으로 제작되었다. 작가가 콜라주로 만들어 내는 모양2에는 기원이 있다. 그것은 법의학책 도판에 있는 무연고자들의 시체, 습하고 어두운 곳에 말라붙은 돈벌레들, 그리고 각기 각색의 방식으로 끝장나는 장면을 중계하는 시어들이다.

차동하의 <축제>가 재현 대상의 정보값을 선연히 보여주는 대신 색면의 운율을 통해 죽거나 남겨진 인간을 위한 시적 공간을

마련했다면, 차연서의 <축제>는 불문율 바깥의 인생들을 모아 “필사”함으로써 자신만의 시어 대장을 구축하였다. (차연서는

세상의 온갖 찌꺼기가 쌓인 쓰레기장에 방문하는 일을 되풀이하며 자신의 “친구들”을 찾아왔는데, 이 모습은 마치 극極과 독毒으로 내공을 쌓는 독거미3를 닮았다.) 번안된 원본은 최소한의 원형을 유지한 채 푹 퍼진 그림자와 같은 인상을 띄었고, 작가는 우리네 세상이란 비극에서 자신의 “그림자극”에 출연할 배우들을 캐스팅하는 일에 늘 설레는 모습이었다.그리고 2025년, 만물이 작게서부터 차오르는 절기인 소만小滿이 지난 후 나와 오진혁 대표는 작가와 함께 그의 서울 작업실과 남양주 작업실을 차례로 방문했다. 그곳에서 나는 (여러분들이 지금, 이 전시에서 보고 있을지 모를) <축제대차>와 <젖은/마른 바퀴> 그리고 <탑>과 <나무>, <대파꽃>을 보았다. 그것들은 그간 내가 따라갔던 차연서의 <축제>와는 다른 성질의 것이었고, 전작에 따라붙은 언어들로 잡히지 않는 행렬 위에 몸을 맡기고 있었다. 갓-태어난 혹은 갓-캐스팅된 연서의 친구들. 서늘하고 따끈따끈하다.

전작과 비슷하면서도 다른 <축제>들로부터 내가 감지한 것은 이전에는 느껴보지 못했던 공간성이었다. 특정한 캐릭터나 장면 그리고 시선을 프레임 안으로 끌어들였던 전작과는 달리 필사의 대상으로 새로이 선발된 석탑, 나무, 대파꽃은 프레임 바깥의 공간으로 자신의 기운을 불어넣고 있었다. 바로 이곳이 차연서의 정원이라는 생각에 나는 어렵지 않게 이르렀고, 필사의 대상으로 새로이 선발된 사물들이 故 차동하의 작업실인 정원을 이루는 요소라는 사실에 주목했다. (23년과 24년에 걸쳐 만들어진 <축제>를 이루는 주요 심상이 사체였다면, 25년에는 남양주의 정원이 또 다른 심상으로서 출연한 것이다.)

아버지가 떠난 장소에서, 아버지가 남긴 재료를 사용한다는 점에서 차연서의 <축제>는 아버지에 대한 애도 작업으로 심심치 않게 취급되어왔다. 하지만 아버지인 차동하의 죽음이 그 세상으로의 입장권이 됐을지라도, 닥종이를 오리는 차연서의 수행을 차동하를 위한 제사로 읽는 일에는 무리가 있다. 그렇다고 본 전시에 출품된 <축제>들이, 2023년도에 제작된 <축제>처럼, 필사의 대상인 시체들의 넋을 위로하기 위한 실제적 애도 행위로 느껴지지도 않는다. 계속해서 이어지고 변모하는 <축제>의 집결지는 과연 어디일까?

작가의 의식을 따라 걷던 나는 장자의 ‘오상아吾喪我’란 개념을 마주했다. ‘내가 나를 장례 지냈다.’ 그리고 ‘내가 나를 잃어버렸다.’라는 뜻의 이 철학은 사회에 의해 만들어진 나我를 잃어버려야 진정한 나吾를 찾을 수 있다는 의미를 담고 있다. 이 원리를 통해 차연서의 <축제>를 바라보자, 작가는 <축제>를 통해 자신이 죽을 때 둘러싸여 있을 풍경을 짓고 있었다. 수많은 법의학 도판과 범죄 프로파일링 자료 그리고 김언희의 시를 접하며 자신이 죽는 장면을 수천 번은 그려봤을 그에게, 작업이란 머릿속의 집을 현실로 불러오는 번역일 것. 각자 제 갈 길을 가던 고아들은 실재적 죽음의 장면으로 점철된 이 정원에서 잠시 한숨을 돌린다.

작가가 “자신은 작업을 통해 적대적인 대상과 화해하는 경험을 수차례 해왔다”고 말한 바 있는 것처럼, 정원을 가꾸는 행위는

현실의 고통과 마주하는 하나의 방식이 되기도 한다. 차연서는 차동하가 만들어온 구버전의 <축제>를 가위로 오려 사체와 정령들에게 바치고 남양주의 정원을 필사함으로써 그 친구들의 몸이 뛰노닐 공간을 증축한다. 최근에 그는 작업을 위해 남양주

정원에 있는 저택에서 며칠씩 거주하고 있다. 그러면서 새로이 만든 작품 사진이나 상념을 내게 문자로 전해주곤 했는데, 얼마

전에는 이 저택에 깃든 성주신이 다시금 웅성거리기 시작했다고 일러주었다. 이제 나에게는 저 말이 또다른 축제의 조짐으로

들린다. 그의 시간선에서 정원-축제의 상이란 굳지 않은 주물처럼 계속해서 달라지는 것이기 때문이다.마지막으로 관련된 재밌는 이야기 하나. 현재 <축제>는 작가를 제외하고 단 두 명에게만 소장되어 있다. 작가는 두 명의 소장자에게 작품을 건넨 후 그 프레임 안에 그려진 사체의 모습이 곧 소장자의 초상화처럼 느껴졌다고 한다. 이에 따르면 <축제>란 곧 소장자의 포트레이트나 드레스 코드와 다름 아닐 것. 거상거상 거상거 는 정원의 모습을 한 축제의 인트로덕션이니, 이 전시 이후에 작가의 새로운 축제가 시작될 때까지 관객인 우리는 이 정원을 게걸스럽게 탐하거나 혼자 있을 때처럼 초연하자. 이러한 우리의 시간이 가능하도록 그가 자신의 정원을 공원으로 열어뒀다는 점 그리고 <축제>를 소장자의 초상화로 여긴다는 점이 차연서가 조직하는 축제의 공공성을 은연중에 환기한다.